Today, we are going to solve Optiver’s challenges from their second installment of their new Prove It series which I have really enjoyed. I will just be providing the mathematical proofs, but if you are interested to see what these formulas and equations mean, please see this video for reference (problems are near the end): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u76c4QDHXME

![]() Prove that for a random walk from

Prove that for a random walk from ![]() to

to ![]() , the expected number of blocks is

, the expected number of blocks is ![]() .

.

![]() For some context, we are walking on the integer number line from

For some context, we are walking on the integer number line from ![]() to

to ![]() where moving one block means moving from

where moving one block means moving from ![]() to either

to either ![]() or

or ![]() . The walk ends when we reach

. The walk ends when we reach ![]() . When we are at

. When we are at ![]() , we automatically move to

, we automatically move to ![]() the next turn. For any other place

the next turn. For any other place ![]() we move to either

we move to either ![]() or

or ![]() with equal probability.

with equal probability.

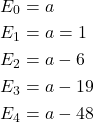

We can encode all of this information using states and expected value. Let ![]() denote the expected value of the number of steps we need to take when at

denote the expected value of the number of steps we need to take when at ![]() before reaching

before reaching ![]() . For

. For ![]() , we have

, we have

![]()

![]()

![]()

To solve this problem, we are going to try and find a closed form for ![]() . Note that

. Note that

![]()

![]()

![]()

Let ![]() . Since

. Since ![]() , we have

, we have ![]() . We now have our

. We now have our ![]() base states and we can recursivly generate the rest of them. For example, using

base states and we can recursivly generate the rest of them. For example, using ![]() , we find that

, we find that

![]()

![]()

![]()

The base cases are trivial (we already did them). Hence, assume ![]() and

and ![]() for the inductive hypothesis.

for the inductive hypothesis.

For the inductive step, compute

![]()

which completes the induction.

So we know that ![]() so all we need is to compute

so all we need is to compute ![]() . Fortunately, recall that

. Fortunately, recall that ![]() Thus

Thus ![]() so

so ![]() . This tells us that

. This tells us that ![]() and specifically

and specifically ![]() as required.

as required. ![]()

![]() What is the expected number of blocks to go from

What is the expected number of blocks to go from ![]() to

to ![]() if the coin is biased and is twice as likely to land on tails.

if the coin is biased and is twice as likely to land on tails.

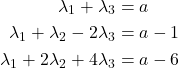

![]() The setup for this problem is exactly the same as the first one, except instead of moving equally likely to

The setup for this problem is exactly the same as the first one, except instead of moving equally likely to ![]() and

and ![]() , we now have a

, we now have a ![]() chance of moving to

chance of moving to ![]() and a

and a ![]() chance of moving to

chance of moving to ![]() if we are at state

if we are at state ![]() . Thus,

. Thus,

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The characteristic equation of the ![]() recursive formula is

recursive formula is

![]()

![]()

which solves to

![]()

Find an interesting solution? Feel free to submit it to Optiver directly at https://optiver.com/prove-it-2