While I was on my 5 hour flight from Virginia to the West Coast, I forgot my headphones and was too frugal to pay for airplane Wi-Fi. So, the only thing I could do on my phone was play Crossy Roads. For the past few months, I had been pretty consistent in collecting the free coins that the game gives you every day and had built up an impressive total of 94000 coins. I thought this airplane flight would be the perfect chance to spend all those coins on the Prize Machine to unlock some new characters to play with.

For those of you that don’t know how the Prize Machine works, you can spend 100 coins on the Prize Machine, and every purchase will yield a character. It’s important to note that it is possible to receive a character that has already been obtained (a duplicate character). In other words, the Prize Machine is like a random draw with replacement. Naturally, the chances of receiving a duplicate mascot increases as you obtain more mascots.

Well, with 5 hours to kill, I just went to the Prize Machine and blew all my coins to try and collect all the characters. I had roughly 60 characters in my collection already and by the end of this process, I had collected 255 with 4000 coins remaining. The only issue was that there were 355 total characters: I was still missing 100.

I thought 94000 coins was a lot, but apparently it wasn’t enough to get all the characters. I started to wonder what was the expected number of coins needed to collect all the characters.

For reference, there are 355 total characters to unlock, but the chicken is given to you at the start of the game and 2 more characters are for in-app purchase only. Furthermore, according to https://crossyroad.fandom.com/wiki/Prize_Machine there are 21 other special characters that cannot be obtained via the Prize Machine. Hence, we need to figure out the expected number of purchases we need to make in order to collect ![]() characters. We can just multiply the number of purchases we need to make by 100 to figure out how many coins we will need.

characters. We can just multiply the number of purchases we need to make by 100 to figure out how many coins we will need.

We will solve the general case of collecting ![]() characters. Let

characters. Let ![]() represent the discrete random variable of the number of purchases until each of the

represent the discrete random variable of the number of purchases until each of the![]() objects are selected at least once, and let

objects are selected at least once, and let ![]() represent the discrete random variable of the number of purchases required to collect the

represent the discrete random variable of the number of purchases required to collect the ![]() th character after

th character after ![]() unique characters have been collected. We have

unique characters have been collected. We have ![]() as a base case and

as a base case and

![]()

Let ![]() represent the probability of getting the

represent the probability of getting the ![]() th character. To start, imagine if we haven’t ever used the Prize Machine before: then we clearly have

th character. To start, imagine if we haven’t ever used the Prize Machine before: then we clearly have ![]() . But after this purchase, we have reduced our odds for getting a new character: it is now

. But after this purchase, we have reduced our odds for getting a new character: it is now ![]() . More generally, after we have collected the

. More generally, after we have collected the ![]() th character, the probability of collecting the

th character, the probability of collecting the ![]() th character with our next purchase is going to be

th character with our next purchase is going to be

![]()

Recall that ![]() represents the discrete random variable of the number of purchases required to collect the

represents the discrete random variable of the number of purchases required to collect the ![]() th character. The key observation is that each

th character. The key observation is that each ![]() is actually a Bernoulli trial and thus follows a Geometric distribution with probability mass function

is actually a Bernoulli trial and thus follows a Geometric distribution with probability mass function

![]()

The notation ![]() reads “follows the distribution” and the notation

reads “follows the distribution” and the notation ![]() is the probability that the first success occurs on the k-th trial. So

is the probability that the first success occurs on the k-th trial. So ![]() means that

means that ![]() is a geometrically distributed random variable with success probability

is a geometrically distributed random variable with success probability ![]() and the probability that the first success occurs on the

and the probability that the first success occurs on the ![]() -th trial is given by the Probability Mass Function (PMF) of the geometric distribution:

-th trial is given by the Probability Mass Function (PMF) of the geometric distribution: ![]() .

.

This is really convenient for us because of the following two facts:

![]() Given a Geometric distribution

Given a Geometric distribution ![]() with probability mass function

with probability mass function ![]() , the expected value is given by

, the expected value is given by ![]() .

.

![]() We have

We have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[E(X)=\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} k\cdot P (N=k)= \sum_{k=1}^{\infty} k\cdot (1-p)^{k-1}p= p\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} k\cdot (1-p)^{k-1}.\]](https://realtrungnguyen.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-5ea5671494e69f87e5be004c6fa75cf2_l3.png)

Note that ![]() and

and ![]() for

for ![]() , so we have

, so we have

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[E(X)=\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} k\cdot (1-p)^{k-1}=p\sum_{k=1}^{\infty} \frac{d}{dp} (-(1-p)^k)=p\cdot\frac{d}{dp}\left(- \sum_{k=1}^{\infty}(1-p)^k\right)=p\cdot\frac{d}{dp}\left(\frac{-1}{1-(1-p)}\right)=p\cdot\frac{1}{p^2}=\frac{1}{p}\]](https://realtrungnguyen.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-cadbe9601d80484c36321e35e4ff898a_l3.png)

![]() Given a Geometric distribution

Given a Geometric distribution ![]() with probability mass function

with probability mass function ![]() , the variance is given by

, the variance is given by ![]() .

.

![]() I won’t provide a proof, but this is a standard result that is taught in many undergraduate probability and statistics courses (MATH 451 at William and Mary).

I won’t provide a proof, but this is a standard result that is taught in many undergraduate probability and statistics courses (MATH 451 at William and Mary). ![]()

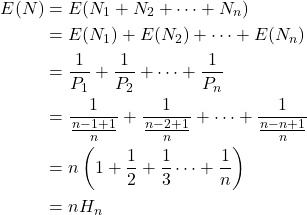

Returning to the problem, since we have

![]()

where ![]() is the

is the ![]() th Harmonic Number. We can approximate the

th Harmonic Number. We can approximate the ![]() th Harmonic Number with

th Harmonic Number with ![]() but it can be more accurately estimated as

but it can be more accurately estimated as

![]()

![]()

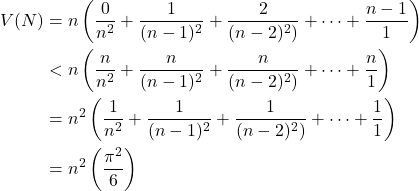

The varience of ![]() can be found in a similar way. Since we have

can be found in a similar way. Since we have

![]()

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[V(N_k)=\frac{1-P_k}{P_k^2}=\frac{1-\frac{n-k+1}{n}}{\left(\frac{n-k+1}{n}\right)^2}=\frac{\frac{k-1}{n}}{\left(\frac{n-k+1}{n}\right)^2}=\frac{n(k-1)}{(n-k+1)^2}.\]](https://realtrungnguyen.com/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-99bf721f07bdb83d28d8420a980d8fcb_l3.png)

but note that

![]()

by the famous Basel problem. So ![]() .

.

Now that we got all the math out of the way, we can answer the original question: what is the expected number of coins needed to collect all the Crossy Roads characters from the Prize Machine? Since the Prize Machine can output 331 different characters per use, we can expect to use it

![]()

import numpy as np

def monte_carlo_prize_machine(characters, num_simulations):

results = []

for i in range(num_simulations):

collected_char = set() # empty set to keep track of collected characters

count = 0

while len(collected_char) < characters:

character = np.random.randint(characters)

collected_char.add(character) # modifies set by adding the specified element if not inside - does nothing if alr in set

count += 1

results.append(count)

mean_result = np.mean(results)

print(f"Expected value of purchases needed: {mean_result}")

monte_carlo_prize_machine(331, 1000)

# Expected value of purchases needed: 2134.584The variance in this value would be

![]()

import math

def purchases_EV(n):

Hn = 0

for i in range(1, n+1):

Hn += 1/i

return n*Hn

def purchases_EV_approx(n):

return n*math.log(n) + n*0.577215665 + 0.5

def purchases_var(n):

return ((n*math.pi)**2)/6

print(purchases_EV(331)) # 2112.059315570107

print(purchases_EV_approx(331)) # 2112.0595673648077

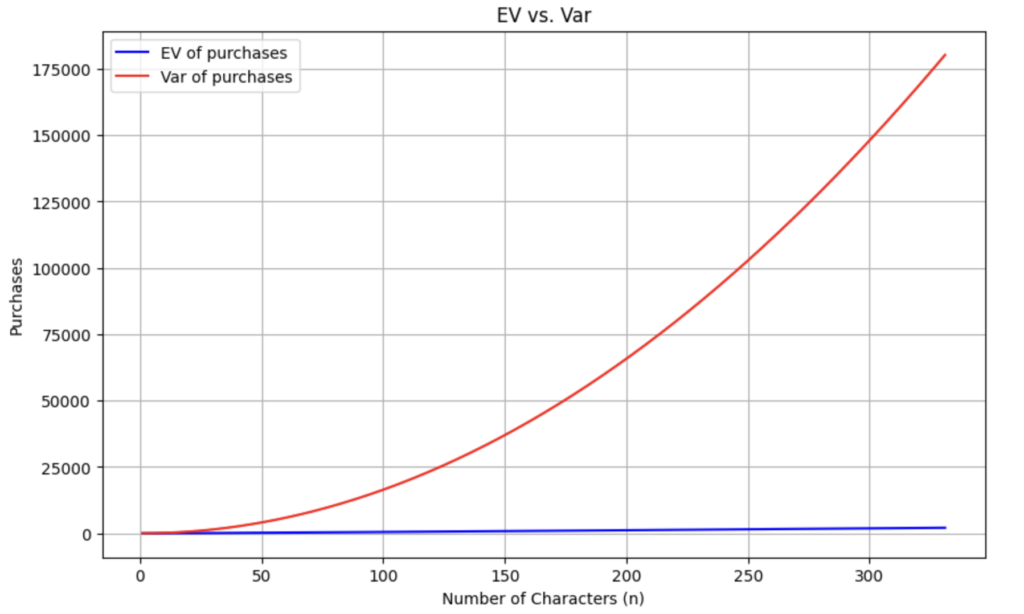

print(purchases_var(331)) # 180220.62129795854The variance grows a lot faster than the expected value since ![]() which is faster than

which is faster than ![]() .

.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import math

# Define the functions

def purchases_EV(n):

Hn = 0

for i in range(1, n+1):

Hn += 1/i

return n * Hn

def purchases_var(n):

return ((n * math.pi) ** 2) / 6

# Generate values for n

n_values = np.arange(1, 332)

ev_values = np.array([purchases_EV(n) for n in n_values])

var_values = np.array([purchases_var(n) for n in n_values])

# Plot the functions

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.plot(n_values, ev_values, label='EV of purchases', color='blue')

plt.plot(n_values, var_values, label='Var of purchases', color='red')

# Add titles and labels

plt.title('EV vs. Var')

plt.xlabel('Number of Characters (n)')

plt.ylabel('Purchases')

plt.legend()

plt.grid(True)

# Show the plot

plt.show()

So, in conclusion, to collect all the animals in Crossy Road, it could take up to

![]()

Maybe on the flight back, I will just play Angry Birds…

Note: Source code for this project can be found on my GitHub here: https://github.com/trippytrung/Crossy-Roads-Prize-Machine